Family migration to the outskirts of large cities is declining

Over the past 15 years, there has been a steady trend towards suburbanisation, with families moving to the outskirts of large cities. At the same time, many rural areas have benefited from the influx of families. However, recent migration patterns show a downward trend.

The housing crisis is beginning to leave its mark on migration patterns. A recent study of migration data by empirica regio GmbH shows that in 2024, the trend of increasing suburbanisation from large cities to surrounding areas was broken for the first time in years. While the net outflows of under-18s from all large cities rose continuously to around 60,000 by 2021, it declined slightly from 2022 and significantly in 2024 to just 44,000.

The outflow of the parent cohort (aged 30 to under 50) from cities also peaked at 112,000 in 2021 and fell to 82,000 by 2024. Here, too, the decline from 2023 to 2024 is particularly pronounced. The decline is not as pronounced among older workers aged 50 to under 65. Here, migration in 2024 was around 16 thousand, slightly lower than in the years 2020 to 2022, when it fluctuated between 19 and 20 thousand.

On the other hand, the net inflow of young adults under the age of 25 into cities has stabilised. While the balance for large cities fell significantly from +76,000 in 2021 to just +57,000 in 2023, it rose again to +65,000 in 2024. Thanks to ‘career starters’ (aged 25 to under 30), independent cities are gaining residents again (+1,900), even if the pre-coronavirus figures of up to over +30 thousand per year (2018) are no longer being achieved.

The fluctuations are smallest among older people aged 65 and over. In 2024, large cities experienced an exodus of around 11,000 people. Between 2016 and 2023, the figures always ranged between 11,000 and 13,000 people.

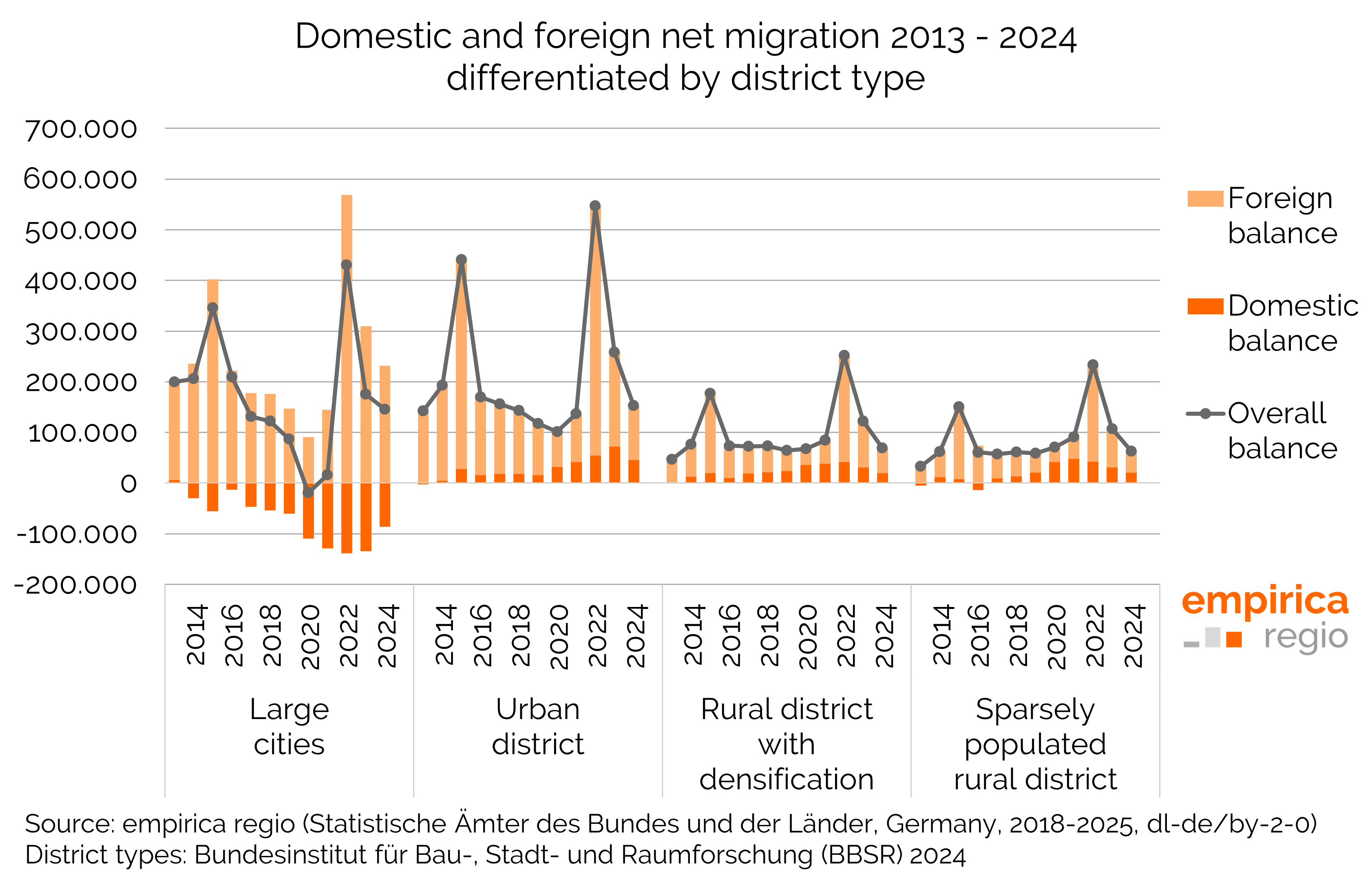

Domestic migration vs. foreign migration in large cities

In terms of internal migration, families and older people continue to move away from large cities, while young people between the ages of 18 and 29 are moving in on balance. However, there are signs of a trend reversal: while the influx of young people is no longer reaching pre-coronavirus levels, the trend towards suburbanisation is also cooling off. In 2022 and 2023, net migration away from large cities peaked at over 130,000 per year, but in 2024 the loss fell to a significantly lower figure of around 87,000.

Furthermore, the population in large cities is only growing as a result of immigration from abroad (with a negative natural balance in almost all cities and years). The current migration data for 2024 shows that, although immigration from abroad has declined significantly since the record year of 2022, it is currently above the level of 2016 to 2019 in all large cities. From 2022 to 2024, however, net migration from abroad to large cities has roughly halved from 569,000 to just 232,000.

Rural areas benefit less from domestic migration

Urban districts and rural areas surrounding metropolitan areas, and in some regions even more remote rural areas, continue to benefit from the exodus of families and older people from large cities. Nevertheless, the declining trend of migration from large cities is also leaving its mark here. Urban districts experienced peak values in foreign immigration (+492 thousand) in 2022 and in domestic immigration (+186 thousand) in 2023, and continued to show a significant increase in 2024. However, gains from foreign immigration have since almost halved to 107 thousand, while domestic migration gains have fallen to just 46 thousand. A similar trend can be seen in rural districts, only at a lower level with smaller migration gains.

Reasons for the trend reversal

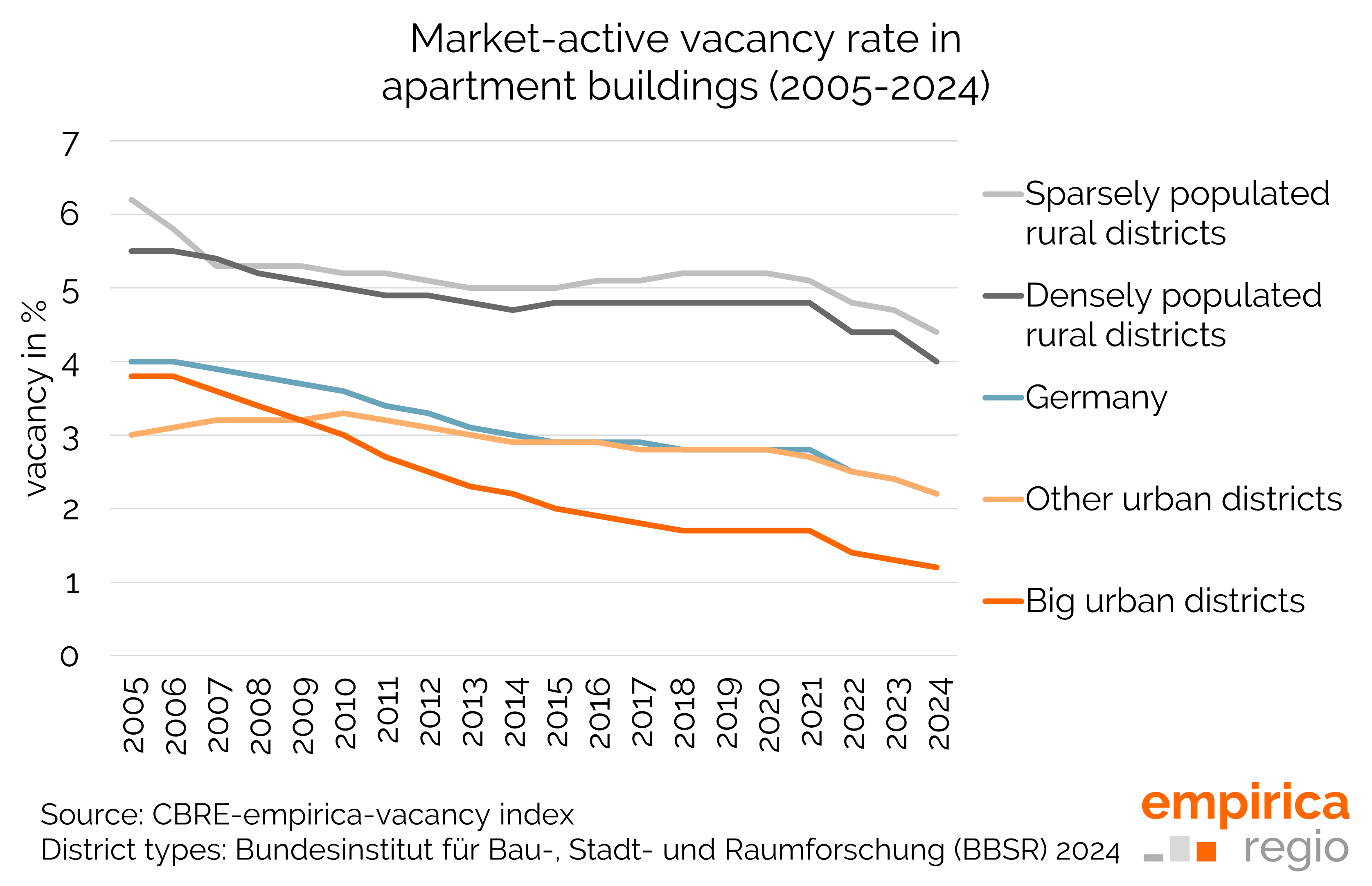

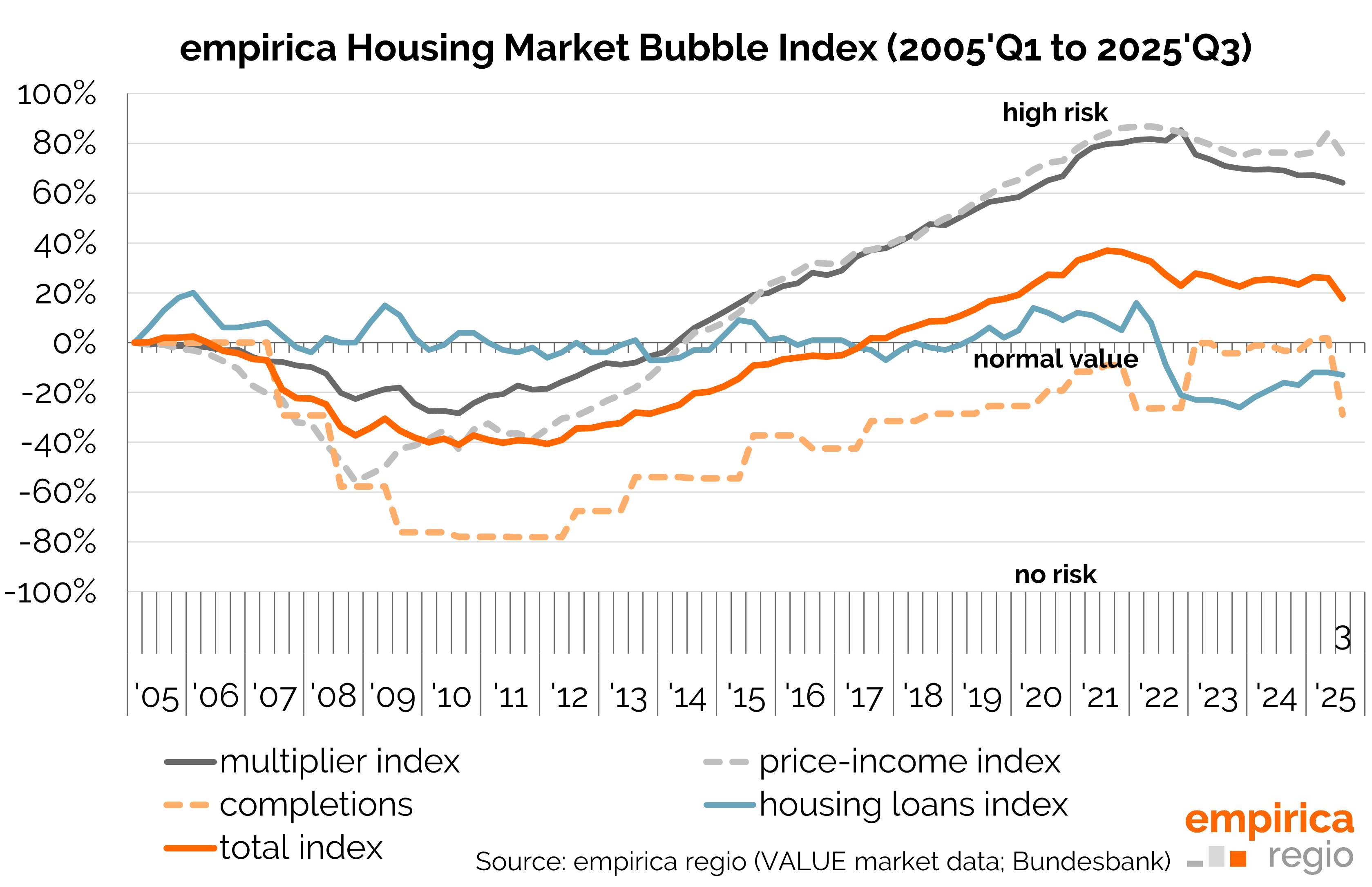

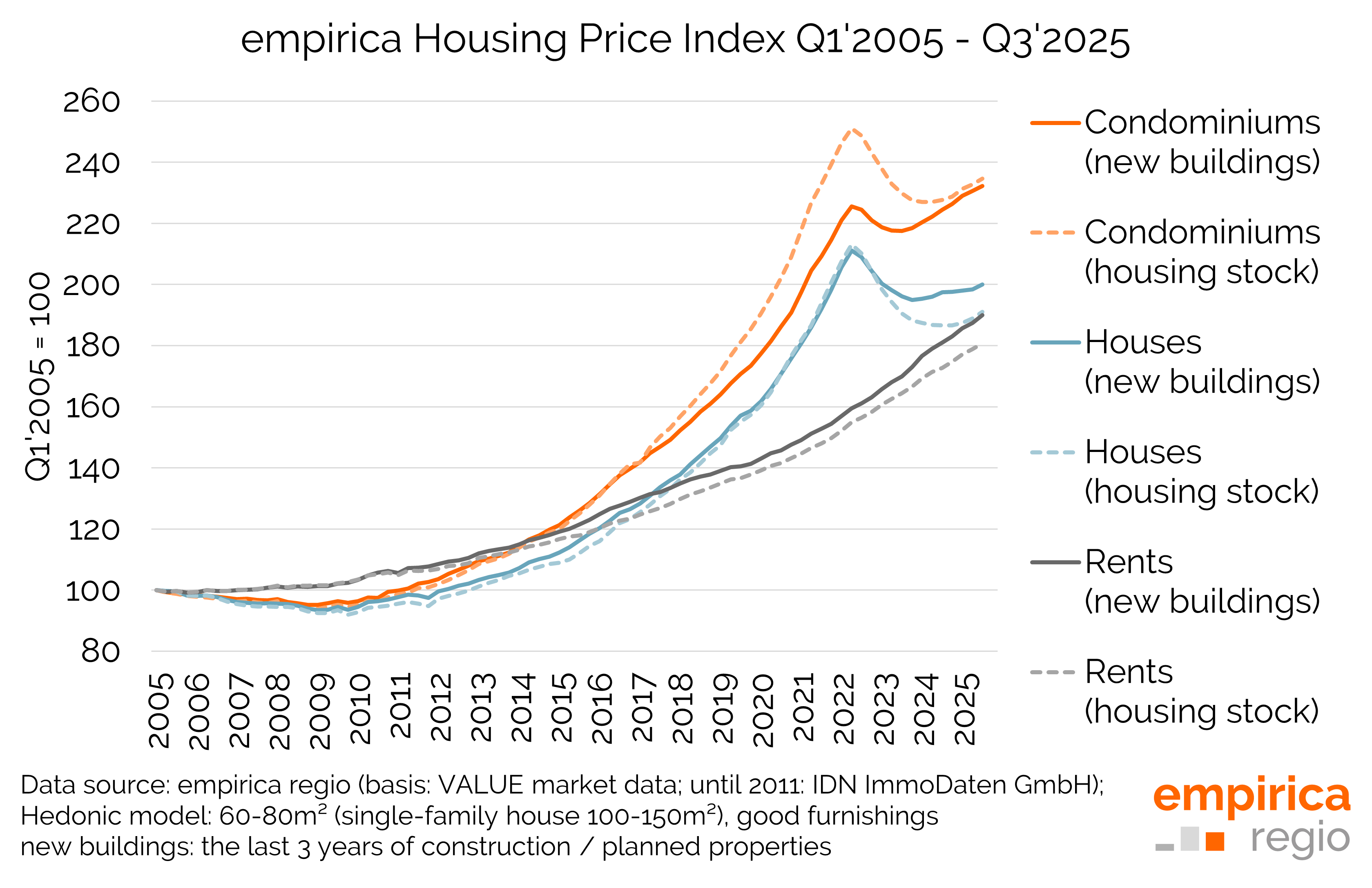

Since the coronavirus pandemic, ‘moving to the countryside’ has suddenly become the new, important trend. However, suburbanisation has essentially continued at the previous level, with only the search radius of households in the surrounding areas expanding in particularly tight housing market regions. But in times of higher financing and construction costs and a significantly reduced supply of new buildings, the suburbanisation trend now seems to be cooling off considerably. As a result, the lock-in effect in large cities is gaining in importance, and the housing market is virtually frozen.

A new empirica paper, which will be published shortly, examines how this new environment affects migration for potential homeowners and thus many families in large cities. We will report on this here in the coming weeks in a second analysis on the topic of migration.